Southeast Colorado Update – 7/8/13

Southeast Colorado Update

Summary of Mineral Lease Activity and Exploration for Southeast Colorado Mineral Owners

July 8, 2013

This is a summary of many news reports from petroleum industry, financial sector and media sources that help to describe what’s going on with petroleum resource development in Southeaster Colorado (SECO) in 2013. We’ve done our best to provide reliable information, but be aware that all of these sources filter their publicity, and may manipulate the content of their releases for marketing reasons or to protect corporate secrecy. Always be on guard about anything that you hear or read, and use due diligence and appropriate caution before making decisions with financial or human consequences. Owners of mineral rights and surface acreage have typically been at a disadvantage because of lack of information about what’s going on in their locality. We hope that this summary helps to bring a little light to your situation.

Mineral Leasing in 2013

Since well before 2011, substantial public and private mineral acreage in southeast Colorado (SECO) was controlled by several major oil companies, and continues to be under long-standing leases. Starting in 2011, a large industry player and several smaller ones saw the potential to use new extraction techniques to reach quality tight oil reserves in the area, and aggressively attempted to aggregate small and large lease holdings in the Las Animas Arch region. Other companies jumped in to reserve leases they intend hold for a few years then flip for a profit. The 2011-12 southeast Colorado mineral leasing frenzy of ebbed in late 2012. In 2011 lease offer bonuses started at around fifty dollars per net mineral acre (nma). In 2012, bonuses ranged from $100 to $300 per nma and royalties were 12-18 percent. Lease periods were 4/4, 3/5 or 5/3 in most cases. Companies with substantial positions in Southeast Colorado are known to be Nighthawk, Pioneer Natural Resources (600,000 acre position), Anadarko (800,000 acre position), Chesapeake Energy, Southwestern, and Devon Energy.

This year, there are only occasional reports of leasing efforts, proceeding quietly and on a small scale. Some very speculative landmen are trying to pick up a few more leases at last year’s prices to flip quickly for five- to eight-fold profit. They see quick money in this kind of move because even in this summer of few bids, the bonuses negotiated in the serious offers to lease are five time higher than the best 2012 prices.

Those prospective lessees who actually plan to drill are determined to get their bits in the ground before the major companies mobilize. They are both small and large companies acting on opportunities in the leases they acquired up through last 2012. Those who are leasing assets in 2013 and plan to drill write their lease offers with shorter periods (3 years, or 3/2), perhaps reflecting their intent to get ahead of their competition. With smaller aspirations and better funding, some of these smaller operators don’t need an eight year lease to act or to sweeten their option to flip the leases to raise quick capital if they find themselves overextended. Royalties are showing at or above 20 percent.

Wells are already being completed and flow tested. Mineral owners report a pattern that Landmen and their corporate clients seem to push extra hard to write new leases just before data on successful new wells hits the press. Each new, productive well raises the value of mineral acreage in the region as a whole.

The timeline of the SECO play appears to be developing similarly to earlier plays in Texas, Ohio, Kansas and the northeast. In those other regions, companies moved fast to acquire rights to mineral acreage while they could still convince owners that their mineral rights were nearly worthless. As each of those plays have proved out with a mounting list of successful wells, the “worthless acreage” argument didn’t work any more, and the price soared for organized, informed mineral owners. In North Dakota, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Texas and other states, the price per nma ranges $3-14,000 per nma in proven plays. As the risk factor is taken out of drilling, and wells provide good production numbers and the price per acre rises. More well data is needed in SECO before we’ll know whether our play will reach these levels. Note that these acquisition prices may realized as one oil company sells their assets to another, or a company makes a large-scale transaction with an organized mineral owner’s association on a proven play. Based on comparable timelines of development in other plays in the Denver-Julesberg Basin, the Bakken formation, the Utica, Eagle Ford and Kansas, the climbing lease prices in 2013 will look like small change as the reports of new wells’ commercial production capacity mount. Leasing activity becomes an arena of large players and big moves where the isolated land owner is just a little guy: hardly noticed and afforded little leverage. One viable and honored strategy is to join an association of mineral owners and negotiate as a block. Good numbers from the new wells in our region are turning the eyes of the exploration and development sector our way, and are sweetening prices in our negotiations substantially over 2012 prices. More new wells and strong well output data needs to come in to command the high prices in SECO that are the norm in Weld County.

For major petroleum companies who are just now turning their attention toward the Las Animas Arch region, getting a large stake in the play is problematic. Acquiring their own position could involve purchasing leased acreage from a competing major player at premium prices.

If you’re approached with an offer to lease your mineral acreage, be sure to have a qualified attorney review the lease before you sign. The leases may appear to be “standard” in format, but they are not. Clauses that are worded in common-sense language may conceal rights for the lessee that could work against your interests, or lock up your land with the lessee with no compensation for you. You should be held harmless from the actions of the lessee. Surface owners’ rights should be protected. If you aren’t already working with a mineral owners’ group, investigate that avenue. Oil companies can work well with a source that allows them to acquire substantial assets efficiently, as has been seen in Pennsylvania and Ohio.

Geology, Technology, and the Potential of Your Mineral Holdings

The current calm in leasing new acreage is accompanied by the sound of drilling rigs probing selected target sites, thus far located in Lincoln, Cheyenne and Kiowa counties. The drillers’ targets are several horizons in the 4000 to 6000 foot deep Mississippian and Pennsylvanian strata around the Las Animas Arch. Established USGS data and fresh 2012 3-D seismic data beckon the drillers to the prospect of multiple, deep, stacked carbon-bearing strata, with measurable potential for recoveries. Worker housing is going up in Cheyenne County. Drilling permits are being filed with the State of Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (COGCC). Access roads are being graded. New drilling in SECO was slow to start because so many crews and rigs were already tied up with contracts in North Dakota, Texas, Kansas, Oklahoma and Ohio.

Security checkpoint at a Kiowa County drilling site

Photo is copyrighted and all rights reserved by the originator. Used with permission.

Oil companies are back in southeastern Colorado, bringing with them new technology and improved techniques to recover even more oil and gas from fields that were tapped decades ago, or were previously considered commercially marginal. Better geological understanding helps to predict large-scale opportunities in shale and lime strata ignored when older, “conventional” drilling was the norm. While there’s still a push to locate the “sweet spots”, mineral owners should be aware that the carbon-bearing layers of the Pennsylvanian and Mississippian layers are not pinpoints, but are broadly-laying zones underlying many counties, rather than a perched, localized deposit to be tapped by a lucky wildcat well.

Some areas may produce more than others, some may not be commercially viable, but the old argument that “your parcel isn’t very valuable because it’s a couple of miles away from a productive well” doesn’t necessarily apply to this new push in petroleum resource development, where ten or twenty mile distances to proven well sites still generate a professional “neighborly interest”. To find the richest locales in our play, Pioneer has a 150 section seismic study in progress around the Las Animas Arch, and there’s another seismic study planned that will run across southern Cheyenne county and northern Kiowa county.

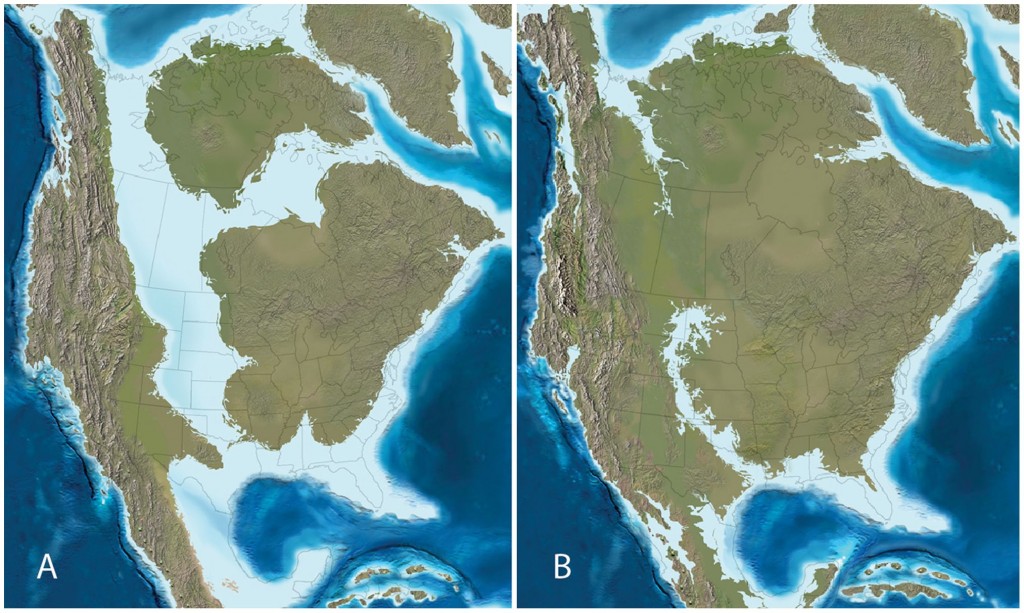

Paleogeographic maps of North America during the (A) late Campanian (∼75 Ma) and (B) late Maastrichtian (∼65 Ma).

Research by Dr. Ron Blakey, Northern Arizona University.

Other credits to: Terry A. Gates, Albert Prieto-Márquez, Lindsay E. Zanno. PLOS ONE. 10.1371/journal.pone.0042135.g001.

Retrieved 21:11, Jul 20, 2013 (GMT).

The petroleum industry success in Kansas has quickly caused the more forward-looking companies to look to Colorado for the western margins of the Late Cretaceous inland seabed that lies a mile below our feet. You can observe a correlation between the maps in the illustration, above, and the the lay of shale, lime and carbonate oil plays in Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, the northern plains states, and the canadian prairie provinces.

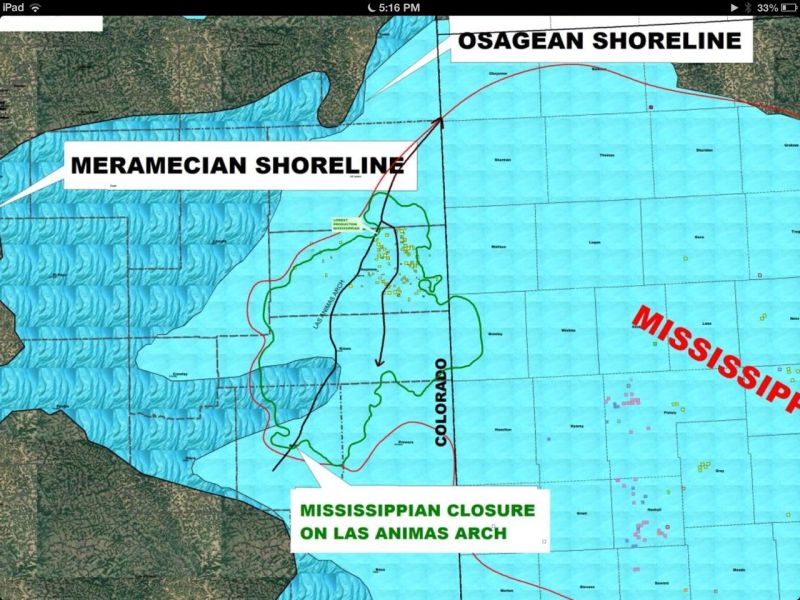

Mississippian Closure on Las Animas Arch

Cheyenne County, Kiowa County and the Las Animas Arch are at the center of this map,

which overlays ancient shorelines over county and state map lines

With recent, intensive exploration in Kansas and Texas a pattern has emerged suggesting that over many millennia, oil migrated horizontally to find greater depth when the geology within a basin permitted it to. In the plains states, this can mean a westward migration, as toward Weld County in the Denver-Julesberg basin, and more importantly, the Las Animas Arch, which Wells-Fargo now refers to as “the soul” of the Mississippian play. Aubrey McClendon, former CEO of Chesapeake Energy and now CEO of Associated Energy Partners made this point relative to Chesapeake’s experience in the Utica, in that the Utica appears to have three phases, or windows, similar to the Eagle Ford Shale in South Texas: a dry gas phase on the eastern side of the play, a wet gas phase in the middle, and an oil phase on the western side. The pattern could apply to the Pennsylvanian and Mississippian plays that stretch from Kansas into eastern Colorado. Watch as the results come in to learn for sure.

New oil well borings are configured for both vertical and horizontal components. In some cases, only the exploratory vertical drilling is done, and the horizontal drilling deferred until the vertical drilling data is analyzed. Sometimes, there’s a benefit to the oil companies to refrain from completing the laterals, and so, avoid publicizing the ultimate productivity of a new well.

Instead of peppering an entire section with wells, horizontal drilling allows an oil company to drill multiple wells in several horizontal directions and even to different horizons from a single pad. In the North Dakota Bakken and Texas Permian Basin plays, such a pad may have half a dozen wells, perhaps more. There’s less disruption of the landscape and lower costs for the drilling operation. Also, it’s easier to manage transportation of oil production from a focused location. To make this technique even more effective, the newest well rigs are fitted with hydraulic bases that allow the well operator to draw the bit out of the ground and inch the drilling rig to the next location on the drilling pad without dismantling and reassembling the drilling rig. It’s technology that’s been built into big mining equipment for years, and it’s a smart application to the oil industry.

In past years, geologist and analysts have commented on the negative impact of excess water production experienced in wells in SECO. “The Mississippian is different from other major shale plays like the Bakken and the Eagle Ford in that it’s not really shale; it’s a carbonate formation. This forces oil and gas companies to think differently about how to best develop the play, seen most readily in how these companies handle water . . . One of the biggest problems producers encounter when developing shale resources is water. However, when it comes to the Mississippian, it’s not the lack of water that’s the problem. In fact, the average Mississippian well only takes about 2.2 million gallons of water to frack, which is less than half the amount needed for an Eagle Ford well. The problem is that that there is too much water which causes producers another set of problems” (Motley Fool, Matt DiLallo, June 28, 2013). That assumption is not holding up in the face of experience out of the field. Improved technology and experience-based know-how have developed “work-arounds” to the water issue. Actual well results in Southeastern Colorado now report low water production at many sites. Some of this success may be the result of lessons learned, such as setting the well target deeper than the overall play, in order to control fracturing that would otherwise open water-bearing layers.

At the same time, costs for the horizontal well drilling phase have declined to the $1 million range per well (a fourth of the $5.4 million cost estimated in 2011) as companies employ the technology and experience gained in the Permian Basin, the Bakken play, Kansas Mississippian Lime, and others. Drillers are finding that wells in SECO are less expensive, just as they’ve been in western Kansas.

Wells Fargo Analysts have projected the estimated ultimate recovery (EUR) of Las Animas region wells to be 120-130 million barrels each.

Drilling and Production Activity

Entrance to Chesapeake’s Nomac operation at the Weimer-State 16-19-47 site

Photo is copyrighted and all rights reserved by the originator. Used with permission.

In Kiowa and Bent Counties, drilling is just getting started. The Weimer well in Kiowa was being turned horizontal and moving toward completion. The rig in use is Chesapeake’s best technology: a $40 million dollar Nomac “Peakerig”. This same rig is scheduled to be moved to the Bent County “Brown” well site this month after it completes the lateral for the Weimer. The #1H Weimer-State 16-19-47, is being drilled south across the section to 9,070 ft. in the Spergen stratum. The well is 10 miles from the nearest existing Mississippian wells in the Wild Sage Brush Field and the Brandon Field. The industry is watching for the results of the Weimer project.

Nighthawk Energy’s Steamboat-Hanson 8-10 well is located in Lincoln County, a reach of the Denver-Julesberg Basin. The announcement of the commercial success of Steamboat-Hanson 8-10 was an industry eye-opener in the first quarter of 2013. Nighthawk now reports that commercial production will begin at its Silverton 16-10 at the Arikaree Creek oil field starting in July 2013. The Silverton 16-10 will draw from a 22-foot pay zone in the Mississippian Spergen formation. In a clear confirmation of its multi-zone strategy, Nighthawk recognized that en route to its goal in the Spergen strata, it had confirmed other oil and gas to recover in the shallower Cherokee formation. Nighthawk’s Snowbird 9-15 will draw from a 24’ thick stratum in the Spergen formation. Nighthawk’s Big Sky 4-11 well began producing over 400 barrels per day with no water production in late May of 2013.

Twenty-two Cheyenne County well permits are on file at COGCC. Private developers have kept news of their well results close to their chests. Chama’s well near Kit Carson, on the other hand, was a publicly-announced success. Per the Denver Business Journal, Rocky Mountain Oil Journal, and HIS, a horizontal well, the Pronghorn State #16-15-48-1H, owned by Chama Oil & Minerals LLC of Midland, Texas, “has reportedly flow tested at up to 2,000 bopd” (barrels of oil per day).” If the Steamboat-Hanson 8-10 was an “eye-opener”, the Chama Pronghorn was a “jaw-dropper”. This was a bigger flow than the “Jake” well that started the rush into the Denver-Julesberg Basin. Chama’s Pronghorn 16-15-48-1H well draws from the same Mississippian formation that’s so productive in southern Kansas, but it’s located near Kit Carson, Colorado, 40 miles west of the Colorado-Kansas line.

The Chama Pronghorn State 15-15-48-1H targets the Pennsylvanian Keyes interval and Mississippian Salem and St Louis Limestone intervals at a maximum depth of 6200 feet.

IHS Inc. reports that Chama is involved in a horizontal Spergen wildcat in Cheyenne County at #1H Kern-State 36-16-46 and is in the permitting process of to drill a horizontal Mississippian wildcat in Kiowa County, Colo.

Be Informed

Be a regular visitor of the COGCC website to check for well permits and results. Stay in the loop with industry publications and websites like the Oil and Gas Financial Journal, the Rocky Mountain Oil Journal, Denver Busines Journal, Oil and Gas Investor, American Oil and Gas Reporter, Wells Fargo news releases and analysis, Nighthawk Energy news releases, Chesapeake Energy news releases, Devon Energy news releases, Motley Fool, and IHS, to name a few. Draw your own conclusions based on the best information you can obtain. We can’t predict whether SECO will produce oil like Weld County or what lease prices will bring in a year. At this point, we can see that there’s a lot of resolve in several oil companies to make southeastern Colorado another pay zone for the industry.

SECORO is a communication network for mineral resource owners of southeastern Colorado. Currently, SECORO communicates with the owners of over 116,000 net mineral acres in Cheyenne, Kit Carson, Kiowa, Bent and Prowers counties of Colorado. The SECORO website is www.secoro.org

These notes are compiled from public, news and industry sources as a partial update to mineral owners covering a variety of aspects of petroleum industry action in southeast Colorado (SECO). Information contained herein is drawn from a variety of published sources and from observations of SECORO participants in the area. In spite of our best intention and effort to relate good and reliable information, the effect of corporate secrecy and calculated filtering of information released by oil companies may cause the content of this report to be incomplete, and possibly contain inaccuracies that we do not knowingly endorse. Please exercise due diligence to verify the reliability of the content of this report before making decisions with financial or human implications.

SECORO provides no legal advice, actionable advice or direction as to land or mineral owners’ decisions regarding management of their mineral interests.

Copyright 2013. All rights reserved. No part of this page may be redistributed, republished, or linked from other websites.

Published Primary and Secondary Sources:

Rocky Mountain Oil Journal

Wells Fargo

Nighthawk Energy

Denver Business Journal

Motley Fool

IHS

Oil and Gas Investor

Rocky Mountain Oil Journal

American Oil and Gas Reporter

Special thanks to our friends, relatives and neighbors in southeast Colorado!